Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life

THE COURTAULD GALLERY, LONDON

10 OCTOBER, 2025–18 JANUARY, 2026

In 1956, Wayne Thiebaud was at the outset of his career as a painter, soaking up the artistic atmosphere in New York while on a sabbatical from teaching at the Sacramento Junior College, when Willem de Kooning offered him a sage piece of advice.

As Thiebaud recalled in a 2021 interview, de Kooning told him that painters often make the signs of art, imitating a style that is already well-established, rather than working towards something that is art; it was a trap he noticed Thiebaud had fallen into with his Abstract-Expressionist-like paintings. De Kooning then asked Thiebaud: Why are you painting, anyway? Because I love it, Thiebaud answered him. That’s not enough, de Kooning shot back, counselling: You must find a subject that you know well and try to deal with it artistically without expecting to get anything from it.

Heeding this, Thiebaud soon returned to Sacramento and to the basics of image making. He began experimenting with Paul Cezanne’s maxim that a painter should “treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.” From there, he teased out confections, slices of pies, cakes, and tarts, as well as other items seen in diners and mom-and-pop bakeries across the country.

Thiebaud sensed that he was onto something by merging the European still-life tradition with a uniquely North American brand of nostalgia but was unsure of the validity of his subject matter. Nevertheless, he continued to hone his approach to color and composition while testing the tactile possibilities of oil paint, exalting these products from their quotidian existence into something close to sacred.

Thiebaud’s harnessing and development of this painterly metamorphosis forms the crux of Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life, at London’s Courtauld Gallery, the first institutional exhibition devoted to his work in the United Kingdom. Even in its brevity—occupying only two rooms, at times it frustratingly suffers from being both too small and too busy in terms of the curation—it is a feat that is immensely pleasurable to watch unfold.

Pinball Machine (1956), the earliest work featured here, opens the exhibition, which follows a largely chronological order. What immediately draws focus is how Thiebaud flattens the volumetric depth of the room in which his painting is set. He segments the expansive back wall in coarse impasto into a large navy-blue rectangle and a narrow, vertical teal rectangle on the left, and denotes the floor with a thin band of red. Jutting out from the centre, cumbersomely, is the titular pinball machine, constructed from two slightly differing vantage points. To its proper left is a gumball machine, and to its right is a stool with a Coca-Cola bottle on it. Despite its inherent disjointedness, the work simmers with potential. In the subjects’ occupation of space and the presence imbued into each station, there is the unmistakable glimmer of the painterly transubstantiation that Thiebaud would make his name from. And seeing this in concert with a work like Jackpot Machine (1962)—a quintessential Thiebaud painting, where he has harnessed this potential—is like learning a magician’s sleight of hand.

In Jackpot Machine, we are presented with a tightly cropped view of a solitary jackpot machine, vaguely anthropomorphic in its form. We see it from a low, almost childlike vantage point, giving it a sense of monumentality that would no doubt play on childhood memories of similar sights in North American viewers’ minds. Thiebaud enhances its monumentality by deploying raking light from the left. He models the harsh shadows in a deep Oxford blue, which he continues to use on the highlights, and to outline the machine. “What the Fauves do when they’re successful is they get the value right,” Thiebaud once explained. “If you get the value right, the darkness or the lightness, you can then use almost any color, hue, or intensity, to fit into that value structure. And that’s, I think, a really great human invention.” Evidently, in the years between these works, Thiebaud equipped himself to be an idiosyncratic evolution of this mode of working.

Thiebaud also made bold advancements in his handling of paint. As evidenced throughout the 1960s, its application became far more controlled and tantalisingly visceral. In Cakes (1963) and Pie Counter (1963) and many others, Thiebaud employs, to mouthwatering effect, a subtler impasto, emulating freshly piped frosting and whipped cream. We spy painterly cues culled from the Impressionists, seen in flickers of yellows, oranges, pinks, and greens that slowly reveal themselves, able to serve both the representation of the machine but also the artistic feast Thiebaud is serving up, triumphantly accentuated by the world-class collection of Impressionist paintings in the adjoining galleries.

Suddenly, after a period revelling in Thiebaud’s prowess, showcased in Jackpot Machine, it dawns on you that the subject matter has dissolved away, and we are engulfed by a rapturous crescendo concerning the mechanics of painting. Except for another early painting, Meat Counter (1956–59), which also acts as a vehicle for mapping Thiebaud’s artistic evolution, all the other paintings on view, to varying degrees, create this same experience.

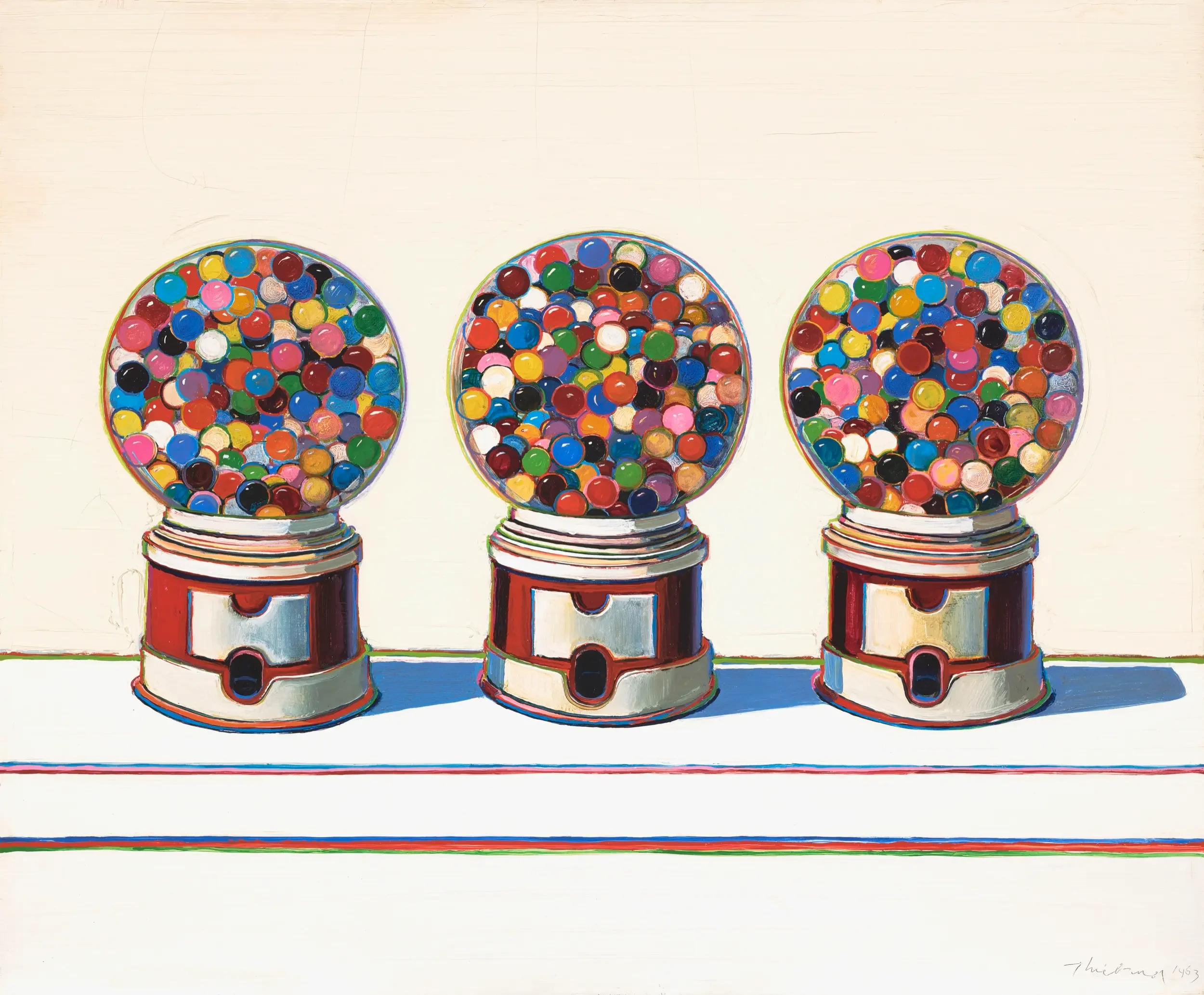

However, for those who venture to see it, a thrilling highlight is seeing the overlaps between Thiebaud’s paintings and the collection of Renaissance works on a lower floor. Many of the visual strategies Thiebaud employed—some gleaned from his time as a commercial art director—have their genesis in the Renaissance, and Thiebaud’s painterly transubstantiation is at its most affecting when it verges towards religious connotations, as seen in Three Machines (1963) and Three Cones (1964). Here, his subjects are displayed on stark white backgrounds, which makes them even more potent, as there is nothing else visually to distract from this transformation. Thiebaud treats each with a Technicolour chiaroscuro and advertising’s “rule of three,” which encourages deep contemplation that plays on religious symbolism. As a result, our investment is rewarded by Thiebaud’s skillset and imagination at its most transcendent.

First published by The Brooklyn Rail

https://brooklynrail.org/2025/12/artseen/wayne-thiebaud-american-still-life/